Article extracted from Asian Diver Issue 02/2020 (155)

Even the deepest of areas have been plagued by plastic

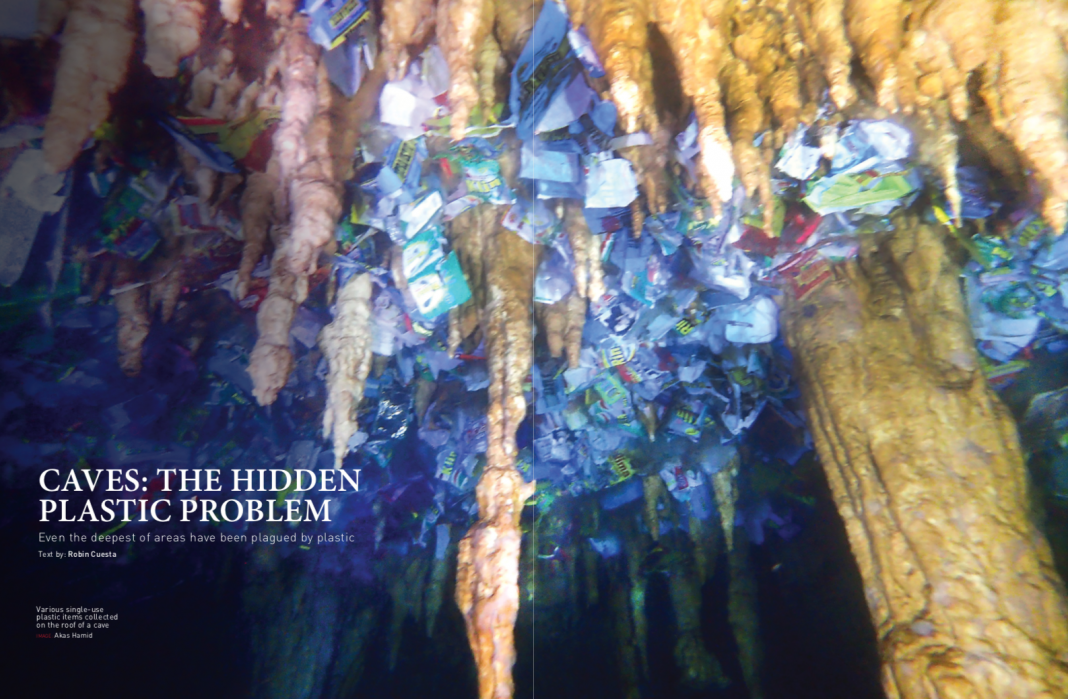

Featured Image: Various single-use plastic items collected on the roof of a cave (IMAGE: Akas Hamid)

Text by: Robin Cuesta

Over the last few years, plastic pollution has become a major issue that has gained a lot of traction across the world. Plastic floating in the Pacific Ocean; a snorkeller swimming in plastic; turtles, sharks, whales in plastic detritus – images of all these things have been popping up on our social media feeds, reminding us of the tragic cost of our wasteful consumerist society. The damage wrought by plastic pollution on ocean life has raised awareness and motivated action. Various global projects and initiatives are trying to working to reduce our plastic consumption and prevent more plastic from entering the ocean.

However, one aspect of the plastic problem has been quite neglected. Less noticeable due to it being underwater, cave pollution, or in other words the pollution of one of our biggest freshwater supplies: underground water.

The sum of all waters on Earth is called the hydrosphere, “is a dynamic mass of water that is continually on the move, evaporating from the oceans to the atmosphere, precipitating to the land, and running back to the ocean again” (Lutgens, Essentials of Geology, 13th Edition, 2017). Our oceans cover around 71 percent of our Earth’s surface and account for about 97.5 percent of Earth’s water (including saline groundwater and lakes). The hydrosphere also includes the fresh water found underground and in streams, lakes, and glaciers, for a total of 2.5 percent of Earth’s water, divided as follows: 1.72 percent in glaciers, 0.03 percent in streams and lakes, and 0.75 percent in groundwater.

Although fresh groundwater represents less than 1 percent of the hydrosphere, it accounts for 30 percent of all freshwater and about 96 percent of all liquid fresh water. In short, it is a vital resource for humankind. To take an example, each day in the US, 1,158 billion litres of fresh water is used. “Groundwater represents the largest reservoir of fresh water that is readily available to humans. Its value in terms of economics and human well-being is incalculable.”

Some regions across the world have access to several supplies of fresh water. Apart from groundwater, lakes, rivers, rainwater collection also serve as water supplies. Some regions don’t have such great fortune and are pushed to rely either on their groundwater resources or on fresh water importation – very often promoted by some major global companies like Nestlé, Danone, PepsiCo, Coca-cola, etc. Southeast Sulawesi (Or Sulawesi Tenggara in the local language), Indonesia, is one such region.

Sitting on a bed of limestone, Sulawesi Tenggara does not have many lakes, rivers or other features to collect rainwater, especially in the south, where the islands of Muna, Buton and Wakatobi lie. However, when you start looking underground, you observe that this region is ridden with thousands of caves, from miniscule to massive openings on the ground, giving us access to its invaluable resource: underground water. Some caves are just a single water point layered in the Earth’s crust, whilst others are openings to an extensive network of caves stretching several kilometres. Often, this lies even beneath the aforementioned cities.

Sitting on a bed of limestone, Sulawesi Tenggara does not have many lakes, rivers or other features to collect rainwater, especially in the south, where the islands of Muna, Buton and Wakatobi lie. However, when you start looking underground, you observe that this region is ridden with thousands of caves, from miniscule to massive openings on the ground, giving us access to its invaluable resource: underground water. Some caves are just a single water point layered in the Earth’s crust, whilst others are openings to an extensive network of caves stretching several kilometres. Often, this lies even beneath the aforementioned cities.

Moreover, when you superpose maps of cave entries and those of cities, one can easily see that cities have been carefully built around these caves. This seems logical as at the time it was the only route to fresh water for drinking, cooking and cleaning.

I began exploring Southeast Sulawesi in 2016, looking for underwater caves. My love of diving and exploration made me quickly realise the scale of the growing problem of plastic in caves. The 200-odd caves I’ve visited (both dry and flooded) has allowed me to connect the dots between human pollution and plastic waste.

Underwater caves in the area can be divided into two groups. One group consists of caves that are far from any human settlement, remaining untouched, clean and unpolluted. The second group includes caves formerly occupied by humans for any activity, which have henceforth become victims of pollution due to misuse.

If we have a look closer at the second category of caves, we realise that the level of pollution is proportional to human density around the cave.

But how is this happening? What are the caves used for? What kind of pollution can we find underground? What are the consequences? How can we fight it? Let’s try to address these questions.

The access to underground water in cities is most likely via a sinkhole. Imagine water dissolving into the ground under your feet and over the course of the next several years, the roof collapses and you can see underground water running under your feet. Now, imagine settlers roaming across the land and finding this point of fresh water in a location with no rivers and no lakes. What an ideal place to settle! Hundreds of years later, cities are built around these sinkholes and concrete stairs are installed for easy access, turning the sinkhole into a vital point of access for the community.

Nowadays, these caves have few different uses, the main one being as a fresh water source. Through pumps or filling of containers, people take this water and bring it to their homes for a wide range of uses like cooking, drinking, washing and laundry. Additionally, people use these water points as a social gathering area.

While chit-chatting and socialising, people do their laundry, take showers or just escape the burning heat of the sun in these shaded areas with cool waters, as young children spend their afternoons swimming.

On top of being a vital life-supporting resource, water is also a social vector, a point where communities exchange and communicate, a gathering place where people from all backgrounds and all social classes mingle and communicate, a place that tends to disappear with our increased use of telecommunications and social media.

As a mainly Muslim country, Indonesia does not offer much spiritual association with water in comparison to Mayan or Chinese cultures, which view underground water as a connection to spirits.

Often, many caves are also listed as tempat wisata, or touristic attractions. They attract both local and foreign tourists. Cave or cave diving tourism is a booming industry in the area, providing a source of income to the locals. But unfortunately the aforementioned reasons have led to polluted caves in Indonesia.

First and foremost, we must acknowledge that plastic packaging has found a place recently and very suddenly in indonesian consumer culture. Before Indonesian began its of rapid development and modern consumption patterns, goods were supported by natural products (like banana or palm leaves, rattan, etc.). Throwing your banana leaf food wrap on the side of the road was totally harmless.

Nowadays, everything is wrapped with plastic – food, soap, detergent, drinks, and worse yet, most household products are wrapped in single-use plastics. Your visit to a cave is accompanied by plastic bottles, styrofoam cups, food containers, snack wrappers, toothpaste tubes, toothbrushes, cigarette butts, PVC pipes, broken glass, electronic waste, batteries – the list goes on and on. Basically, everything that people use on a daily basis ends up down here.

While such waste accumulates at the entrance of underwater caves, in some cases, the current can push garbage deep into the cave.

I once found plastic wrapping more than three kilometres deep inside a cave, submerged underwater.

The consequences are terrible on all levels. For one thing, the garbage makes such places look unsightly, hence lowering the potential attraction to tourists. Nobody wants to visit a place littered with plastics.

Then come the consequences affecting the quality of water. Plastic can remain underwater for hundreds of years and never completely disintegrate. At some point, they turn into microplastics, too small to be detected by the eye but big enough to be ingested by fish or humans.

During my explorations and clean-ups, I have found plastic packaging dating back 30 years that is still in perfect condition. In several places deep inside some caves, I have also noticed bacteria growing and foam forming because of the heavy use of chemical detergents in the water. And not unsurprisingly, the more pollution that I have observed, the less abundant the marine life found in the caves. I haven’t assessed that observation with scientific backing, but the results were pretty clear to me.

On a brighter note, caves that I have cleaned up have quickly seen the appearance of more marine life.

Ultimately, it is the hazard to human health that is the biggest threat from plastic and chemical pollution. Without even considering the bacterial contamination, boiling does not impact microplastics, which remain invisible in the water, adversely affecting our health in unforeseen ways.

While efforts are being made to protect the ocean, providing tourism related income and as a source of food, caves and underground water is largely being overlooked, instead of being treated as the critical and vital resource that it is.

Still, some conservation groups are becoming more focused on preserving freshwater resources and emphasising its importance for local communities. Education is key, but non-governmental organisations coming in and telling people how to behave, what to do and what not to do, isn’t a long-term solution. Behaviours and social relations in local communities are based on thousands of years of history. We need to learn about this together and collaborate with local communities to find ways to improve the situation.

Instead of saying “you should not do that” we must work together to find alternative solutions without altering the social role of these freshwater resources and propose alternatives instead of prohibiting them.

In the short run, caves have to be cleaned up, and quickly. Nobody can argue about that.

Since I began exploring caves in 2016, and more frequently since starting my own dive operation in Sulawesi Tenggara, I’ve been organising underwater cave clean-ups along with fellow divers in Baubau. I try to involve people around me at the same time. It has been quite successful, though on a very small scale.

Our group of qualified cave divers bring the collected trash to the surface and then people help to haul the garbage out of the water, as well as clean up the dry mouth of the cave.

I’ve calculated that one man can remove around 20 kilograms of trash per hour from a cave if working hard, while I estimate the total amount of trash in these few underground networks to be on the order of tonnes. Do the math: It is a titanic job.

The main issue of organising cave clean-ups is the technical nature y of the job. Only certified cave divers are able to do the clean-up, and only a handful of people are certified in the local area. Fellow cave divers flying down could be a solution, but it would require money. Part of the solution would be to put signs and trash bins at the cave entrance area.

We can also fund education initiatives, and get people of all ages to realise that plastic in our oceans is a problem. Engaging them with short educational films about the trash that has collected underground is one way. Ideas are numerous. But so far everything has been done on everybody’s free time, without any other incentive other than trying to save our water resources and halt the plastic tragedy that is unfolding beneath the surface. We do need to find ways to fund our conservation projects so that they can be executed on a larger scale.

Eventually, all the initiatives will have to come from the top. Indonesian society is well structured and authority is recognised and respected. Having local leaders on board is a must to make things move forward. We’ve been working hard to raise awareness about the issue with the heads of villages, parliament representatives, bupati (the local governor) and the of relevant ministries of environment, health, and tourism. Things are slowly moving forward.

Every small step is a victory, and we cannot just change everything overnight. The young generation is very receptive and their dynamism and enthusiasm regarding marine conservation and preserving freshwater resources is heartwarming. I truly hope that one day they will have clean waters in clean caves, and that they will be able to safely enjoy our most vital resource on Earth.

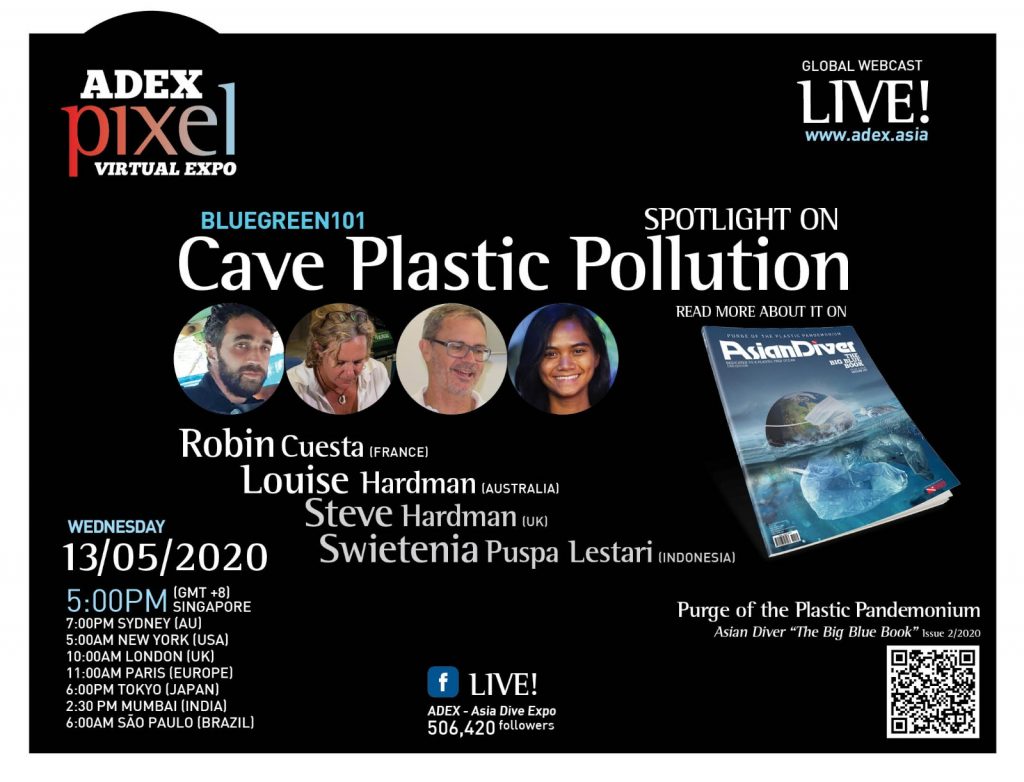

Like what you’ve read so far? Check out our LIVE! Panel Discussion on Cave Plastic Pollution on 13 May 2020 at the following times:

Singapore – 5PM / Sydney – 7PM / New York – 5AM / London – 10AM / Paris – 11AM / Tokyo – 6PM / Mumbai – 2.30PM / Sao Paolo – 6AM

This panel features:

Julien Fortin (#France)

Owner of Technical Diving India, PADI Course Director & Tec Instructor Trainer, TDI & IANTD Technical & Cave Dive Instructor, Global Underwater Explorer (GUE) Fundamentals Instructor

JULIEN FORTIN is a PADI Course Director and Tec Instructor Trainer, TDI and IANTD technical and cave diver instructor, and a Global Underwater Explorers (GUE) Fundamentals instructor. He is currently splitting his time between India and Mexico where he works on various teaching and exploration projects but has taught numerous courses in various countries in Asia, America, and Europe. He runs Technical Diving India and has trained dozens of technical divers in India up to the Trimix level. Quality-oriented, dedicated to team-diving, standardized procedures, and the usage of helium-based mixes to support aggressive diving, he is an active member of the community and devoted to growing a network of like-minded divers. Having lived in various European, Asian, African, and Central American countries, his background spans from engineering and sustainable development to information technology, languages, and various inter-cultural interests.

Brian Kakuk (#Bahamas)

Co-owner/Operator of Bahamas Underground (Cave & Technical Diver Training Facility) on Abaco Island, Founder/Director of The Bahamas Caves Research Foundation, a Non-Profit Exploration, Research, Conservation & Education Foundation conducting exploration in underwater caves and blue holes in the Bahamas (since 1990)

BRIAN KAKUK is the founder/director of the Bahamas Caves Research Foundation and the co-owner/operator of Bahamas Underground Cave and Technical Diving Facility. Brian is a former U.S Navy Diver with 37 years of underwater military, exploration, science, and film experience. A Fellow of the Explorers Club of New York, Brian is also an author, photographer, Diving Safety Officer, underwater researcher, and conservationist. Brian is a Cave Diving Instructor for the National Speleological Society – Cave Diving Section (NSS-CDS) and an Advanced Cave Instructor and Instructor Trainer for the International Association of Nitrox and Technical Divers (IANTD) He is also on the International Board of Advisors for IANTD.

Jill Heinerth (#Canada)

Underwater Explorer and Filmmaker

JILL HEINERTH is an underwater explorer, writer, photographer, speaker, and filmmaker. A pioneer of technical rebreather diving, she has led expeditions from inside icebergs in Antarctica to diving into an active volcano. Jill is the first Explorer-in-Residence of the Royal Canadian Geographical Society. Her book, INTO THE PLANET, has been lauded by the Wall Street Journal, Oprah Magazine, and the New York Times. Jill is a Fellow of the International Scuba Diving Hall of Fame, Underwater Academy of Arts and Sciences, Women Divers Hall of Fame, National Speleological Society, and the Explorers Club which awarded her with the William Beebe Award.

Sam Meacham (#Mexico)

Director of El Centro Investigator del Sistema Aquifero de Quintana Roo, AC. (CINDAQ), Global Underwater Explorers (GUE), The Explorers Club Fellow, NASA Space Grant Fellow, National Geographic Explorer/Grantee

SAM MEACHAM is the Director of El Centro Investigador del Sistema Acuifero in Quintana Roo, Mexico. An experienced cave diver, he remains committed to understanding the complex dynamics of the Yucatán Peninsula’s karst aquifer, as well as the people affected by it. He has extensive experience leading cave diving expeditions in the region, the most significant of which is the ongoing exploration of Sistema Ox Bel Ha and the adjacent Sian Ka’an Biosphere Reserve. Sam earned a Master’s Degree in Science in Natural Resources in 2012 from the University of New Hampshire, and he has been a Fellow of the Explorers Club of New York since 2000, a NASA Space Grant Fellow, and a Best of Adventure Honoree in 2008’s National Geographic Adventure Magazine. Sam has appeared in documentary films for CNN International, The Discovery Channel, PBS, NHK, National Geographic, BBC, and BBC’s Natural History Unit, including the critically acclaimed “Planet Earth” series.

Robin Cuesta (#France)

Owner of Sulawesi Technical Diving, Founder of Indonesia Cave Diving Association, Technical Cave Diving Instructor – IANTD

ROBIN CUESTA is the only active Technical Cave Diving Instructor currently operating in Indonesia. He started exploring caves in Sulawesi three years ago, and never stopped since then. His passion had led him to unravel unexplored caves all over the country, from Sumatra to Papua passing by Java and Sulawesi. He recently opened the first “Rebreather, Technical and Full Cave Diving Training Center” in Indonesia, and helps to develop cave diving interest and education among the local community through the Indonesia Cave Diving Association.

Bruce Konefe (#USA)

Owner of Deep Tec Diver, Technical Instructor Trainer Director – CCR, Wreck, Cave Diving, ANDI ITD

BRUCE KONEFE is a pioneer technical cave and deep wreck, side mount, and rebreather Instructor Trainer- with over 25 years of full-time experience planning and organizing the most ambitious technical diving expeditions throughout most of Asia. Alongside planning and organizing expeditions has 6 years experience as an ANDI Instructor Trainer Director. Over the past 2 decades, I have been fundamentally involved in the development and evolution of technical diving in Asia. Not only have I taught a generation of technical divers and Instructors, but I have also been involved in the development of multiple technical training courses, mapping virgin caves, discovering, and surveying mystery wrecks.

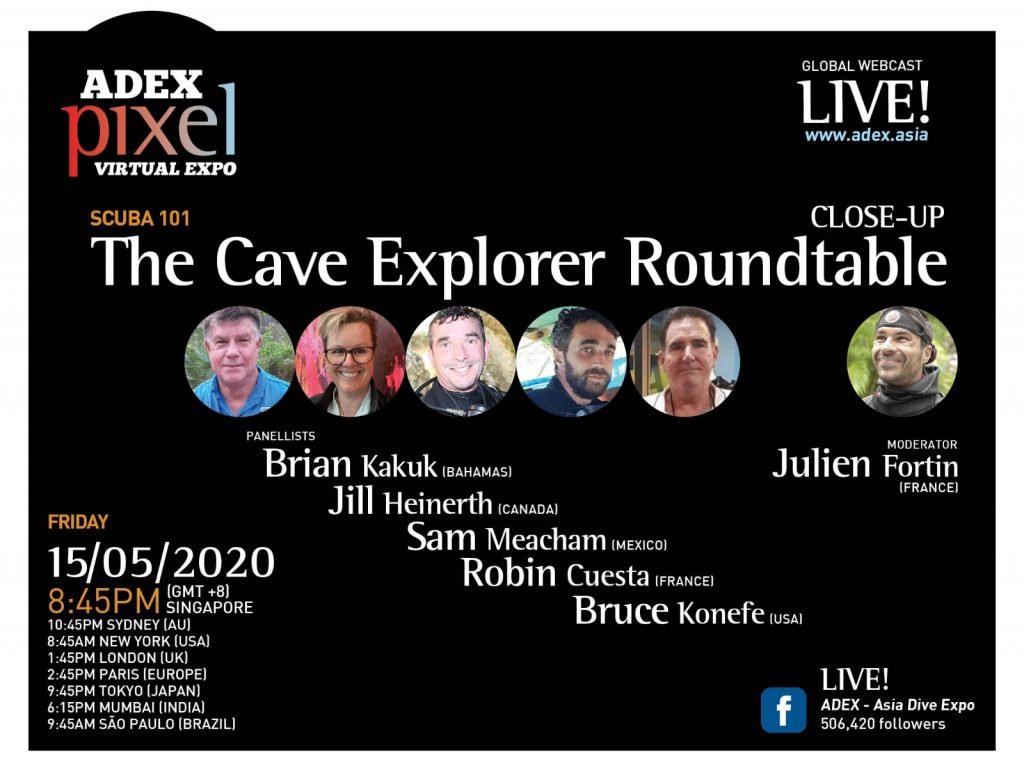

Craving more cave-exploration? Tune into our LIVE! Panel Discussion on Cave Explorer Roundtable on 15 May 2020 at the following times:

Singapore – 8.45PM / Sydney – 10.45PM / New York – 8.45AM / London – 1.45PM / Paris – 2.45PM / Tokyo – 9.45PM / Mumbai – 6.15PM / Sao Paolo – 9.45AM

This panel features:

This panel features:

Robin Cuesta (#France)

Owner of Sulawesi Dive Trek, Member of Indonesia Cave Diving Association, Technical Cave Diving Instructor – IANTD

Robin Cuesta is the only active Technical Cave Diving Instructor currently operating in Indonesia. He started exploring caves in Sulawesi three years ago, and never stopped since then. His passion had led him to unravel unexplored caves all over the country, from Sumatra to Papua passing by Java and Sulawesi. He recently opened the first “Rebreather, Technical and Full Cave Diving Training Center” in Indonesia, and helps to develop cave diving interest and education among the local community through the Indonesia Cave Diving Association.

Louise Hardman (#Australia)

Founder & CEO, Plastic Collective

Louise Hardman is the founder of Plastic Collective, a social enterprise determined to stop plastics entering the oceans. Louise is a scientist, educator, and innovator, who has become an expert in grassroots community engagement, the chemistry of plastics and the circular economy. Louise continues to speak locally and internationally, sharing her message with passion about opportunity, empowerment, innovation, and hope. With more than 8 million tonnes of plastic waste entering the world’s oceans every year, Louise’s vision of how to stop plastic becoming pollution is one that resonates with everyone she meets.

Steve Hardman (#UK)

Chairman & CFO, Plastic Collective

Steve Hardman is a serial entrepreneur who has built a number of major technology businesses in the automotive, motor racing, and software sectors. Brother of Louise, Steve grew up on East Coast, Coffs Harbour, and is now based in London. His last venture was developing online video delivery and monetizing technologies to the European tv broadcasting industry.

Swietenia Puspa Lestari (#Indonesia)

Founder and Executive Director, Divers Clean Action

Swietenia Puspa Lestari, the 25 years old woman who graduated from environmental engineering in the Institute of Technology Bandung, founded Divers Clean Action community since November 2015 and NGO since 2017. Her hobby on scuba diving made her together with 1.500 volunteers across South East Asian countries and of course, Indonesia, to combat marine debris issues with various actions such as research, campaigns and workshops, community development, and collaborations with private sectors to governments. Through these works she leads, Tenia is inaugurated as Top 100 Inspiring & Influential Woman BBC 2019, and 30 under 30 Forbes Social Enterprise Asia 2020.

Don’t miss out on these exciting discussions – See you there!